All posts

The Cure for America's Healthcare System

Mary McQuilkin, NP, MPH

Apr 6, 2020

10 min

What is primary care?

Primary care is your first point of entry into the medical system when you have a new health issue that hasn’t been diagnosed yet, and it’s where you go for preventive care, health screenings, and treatment for chronic conditions. Research has shown that people who have a primary care provider (PCP) are healthier, go to the emergency room less often, and live longer.

The goal of primary care is not just to treat specific diseases, but to develop a relationship between a patient and their primary care provider over time in which the PCP helps the patient improve their overall health. This relationship between a patient and their PCP has been shown to improve patient outcomes (e.g. better diabetes control, fewer heart attacks, less measles).

This is partially because continuity of care over many years allows the PCP to really get to know you and your health. This includes social determinants of health — a stressful family situation, exposure to chemicals at work, or living in a neighborhood where it isn’t safe to exercise outside — factors that impact your health, but which take time to know about a person. Continuity is also helpful to observe subtle changes over time, such as a mole growing and changing shape or a new heart murmur you didn’t have during your wellness exam the year before. Another way having a PCP improves outcomes is through improved communication and the higher likelihood that you will try a recommended medical treatment or lifestyle change if it was made in the context of a relationship with a professional you know and trust.

The vast majority of healthcare can be provided within the primary care office. If you have a complex health issue or a need outside of your PCP’s knowledge and training, they’ll write you a referral to a specialist to ensure you get the care you need. For example, a physical therapist can help you recover from a back injury, or a rheumatologist may manage an autoimmune disease such as lupus. The specialist then sends notes back to the PCP with their advice on management of the patient’s condition — whether it’s strength training exercises, or medications. Primary care providers coordinate care with specialists and other members of a patient’s care team to ensure everyone is safely and effectively working together to help the patient reach their health goals.

Why is primary care important?

The United States spends more per capita on healthcare than any country on earth, yet we have the worst health outcomes of any developed nation. This is both because we pay more for the same services and medications, and because our healthcare system doesn’t focus on prevention of disease and early treatment in primary care, which saves most countries, such as those with universal healthcare, a lot of money.

It isn’t just about money and medical debt causing most bankruptcies, though. Americans have a lower quality of life when they live with conditions such as obesity, diabetes, and heart disease. Most American adults live with a chronic medical condition, and 40% have 2 or more. Chronic diseases are what most Americans die from, but they are preventable.

It isn’t just about money and medical debt causing most bankruptcies, though. Americans have a lower quality of life when they live with conditions such as obesity, diabetes, and heart disease. Most American adults live with a chronic medical condition, and 40% have 2 or more. Chronic diseases are what most Americans die from, but they are preventable.

Four behaviors are to blame for 40% of chronic disease in Americans: smoking, excess drinking, unhealthy diet, and lack of exercise.

Working with your PCP on health behavior change can improve quality of life and prevent most chronic diseases from developing. If a disease does develop, such as diabetes, catching it early prevents complications like kidney disease. The earlier a person gets treatment, the more likely they are to still be able to live a full life free from disability. The continuity primary care provides is ideal for managing chronic conditions like diabetes and high blood pressure, which need to be re-evaluated over time and require sustained diet change, physical activity, and medications for optimal control.

Lack of Access to Primary Care in the U.S.

Even after the Affordable Care Act was passed, many Americans still don’t have health insurance, and even more are underinsured, meaning they have out of pocket costs that are unaffordable, so they still can’t get the care they need. Among the people who got insurance through their employer in 2018, 28% were still underinsured. In 2020, a look back at the last decade shows that primary care visits have decreased by nearly 25% in recent years, likely due to more plans charging co-insurance and higher co-pays for visits. This will lead to more problems later as opportunities for preventive health and screenings are missed, and people wait for conditions to progress to the point of needing to go to the ER or be hospitalized. Lack of health insurance coverage and access to care doesn’t affect everyone equally. There are large disparities based on race and income in the U.S.

KFF

KFF

Primary care is associated with a more equal distribution of health in populations. Countries with universal access to primary care see differences in health outcomes between whites and minorities decrease or disappear. In the U.S., African Americans and other minorities have poorer health outcomes compared to whites for nearly all health metrics.

Communities with more PCPs are healthier when measured by metrics such as ER visits, heart attacks, and hospitalizations. On the contrary, communities where there are few PCPs and people access care directly from individual specialists have more health disparities, and poorer health outcomes overall.

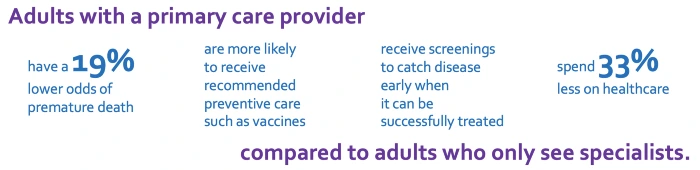

This is counterintuitive; you might expect that low-income people and minorities in a community with a PCP shortage would be disproportionately negatively affected, while the wealthy people would still be able to get high-quality care, but this is not the case. Getting care only from specialists is associated with a 19% higher odds of premature death compared to adults who go to their PCP for most care. Specialists don’t coordinate a patient’s overall health with holistic, comprehensive care; they typically only provide services within their specialty. For example, if you go to a gynecologist instead of your PCP for a pap smear to screen for cervical cancer, she likely will also talk to you about breast cancer screening, but may not screen for diabetes or depression like your PCP would. People without a PCP miss out on recommended preventive health services.

While primary care is the foundation of healthcare in most countries, the U.S. instead shifted to a system with many specialists after WWII. Less than 1/3 of practicing physicians in the U.S. work in primary care, and a dismal 33% of medical school graduates choose to go into pediatrics, family medicine, or internal medicine. This is in part because the salary is about half what a specialist makes, and being a PCP comes with responsibility and long hours. This is unfortunate for our nation, both because the shortage of PCPs is expected to keep increasing, and because communities who get care from specialists instead of PCPs have worse health outcomes.

Types of PCPs

All primary care providers are licensed to diagnose, prescribe medications, order labs and imaging studies, and write referrals to specialists when needed. There are some general differences in the training of professionals that provide primary care, summarized below. Individual PCPs also bring their own specialized knowledge, education, and experience to their practice. Within professions, there is variability in knowledge and scope of practice between individuals. For example, not all MDs perform routine pelvic exams, and some providers have additional certification in the treatment of certain diseases or populations. It is important to find a PCP who is a good fit for you — both personally and in terms of your medical needs — so I recommend reading about providers before scheduling an appointment.

- Doctor of Medicine (MD): MDs are licensed physicians who have completed 4 years of medical school. The first two years focus on the sciences, while the second two years focus on clinical training. MDs can practice independently after completing a 3-year residency in family medicine or internal medicine, but some choose to further their training with a fellowship program where they gain more experience in a specific specialty, such as obstetrics.

- Physicians Assistant (PA): PAs are licensed to practice in collaboration with a physician after completing a 2-year masters degree program. The PA school curriculum is modeled after medical school, which involves both didactic and clinical training. Like the other types of PCPs, PAs also take a national boards exam and are licensed by the state to practice.

- Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine (DO): DOs are licensed physicians who have completed 4 years of osteopathic school, which emphasizes the musculoskeletal system more than traditional medical school and includes training in non-western practices such as osteopathic manipulation. The first two years focus on the sciences, while the second two years focus on clinical training. DOs can practice independently after completing a 3-year residency, but some choose to further their training with a fellowship program where they gain more experience in a specialty.

- Nurse Practitioner (NP): NPs are licensed advanced practice registered nurses who have completed 4 years of nursing school. The first two years of nursing school focus on the sciences, while the second two years focus on clinical training. After passing a national boards exam to become a registered nurse (RN) and earning state certification, most work for 1-3 years as RNs before entering NP school, which is 2–4 more years. Graduate study builds on nursing school to expand on the RN scope of practice to include independently diagnosing, prescribing, and providing primary care for patients in the nurse practitioner role. After earning a masters degree or doctoral degree, a national boards exam and state certification are needed to practice as a NP.

California is the only Western state that requires NPs to have a business contract with a physician, known as a collaborative practice agreement, which requires standardized procedures okayed by a MD (even though we have national standards that specify our scope of practice) and prevents NPs from opening their own clinics in rural and low-income communities where there are few MDs. While 60% of CA NPs reported this restriction doesn’t prevent them from using their own license to diagnose, prescribe, and care for individual patients, it does limit access to primary care for underserved populations.

Nurse Practitioner Scope of Practice Restrictions by State

Nurse Practitioner Scope of Practice Restrictions by State

For example, if a NP has additional training and approval from the DEA to prescribe buprenorphine to treat patients with opioid use disorder, but the collaborating physician does not (only 3% of primary care MDs have set aside the 8 hours needed to earn their DEA waiver), then the NP cannot prescribe this medication in CA, which is one of the best therapies we have to combat the opioid epidemic. Meanwhile, only 10% of Americans seeking treatment for opioid use disorder have access to it.

The NP role was developed to send experienced nurses with additional training to areas where there are no doctors; Mary Breckenridge paved the way by riding on horseback over mountains to deliver babies and check on new mothers in rural towns. Later, in Colorado, Loretta Ford advocated for and earned the legal recognition of the NP role. In 1986, the Office of Technology Assessment cited more than 250 references in their report concluding that NPs performed as well as MDs on patient outcomes including diagnosis, management of medical conditions, frequency of hospitalization, and patient satisfaction. In the decades since, an even larger body of research has consistently shown that NPs provide primary care that is safe, of equal or higher quality compared to care provided by MDs, and lower cost. People who live in states without restrictive NP scope of practice laws have more access to primary care, fewer emergency room visits and hospitalizations, and receive safe, high-quality care.

The NP role was developed to send experienced nurses with additional training to areas where there are no doctors; Mary Breckenridge paved the way by riding on horseback over mountains to deliver babies and check on new mothers in rural towns. Later, in Colorado, Loretta Ford advocated for and earned the legal recognition of the NP role. In 1986, the Office of Technology Assessment cited more than 250 references in their report concluding that NPs performed as well as MDs on patient outcomes including diagnosis, management of medical conditions, frequency of hospitalization, and patient satisfaction. In the decades since, an even larger body of research has consistently shown that NPs provide primary care that is safe, of equal or higher quality compared to care provided by MDs, and lower cost. People who live in states without restrictive NP scope of practice laws have more access to primary care, fewer emergency room visits and hospitalizations, and receive safe, high-quality care.

There is no evidence that requiring NPs to have collaborative agreements with MDs or MD supervision improves patient safety or quality of care. MDs can bill up to $15,000 a year per NP for these agreements, even though the MD is not required to work in the same county as the NP, much less provide supervision of any kind. A large national survey found that 77% of primary care MDs support unrestricted practice for NPs. The only opponent of full practice authority for NPs, a well-funded lobbying group, has cited unfounded fears, rather than an evidence-based concern for the health of the communities they entered the profession to serve. There is currently a bill in the CA state legislature to remove the collaborative practice agreement requirement for NPs, which would not change the scope care we already provide safely for our patients as primary care providers every day, but would allow NPs to open their own practices.

There is evidence that NPs are more likely than MDs to live in rural and urban low-income communities, and efforts to draw MDs to these underserved areas have repeatedly failed. Interestingly, this is in part because MDs tend to marry professionals who need to work in urban centers, while NPs are more likely to be at home in communities with a PCP shortage. Nurse practitioners in states that allow full practice authority are more likely to practice in primary care, in rural areas, and areas with lower socioeconomic and health status. Removing NP scope of practice restrictions will improve the health of all Californians by increasing access to safe, high-quality primary care, especially for communities with the greatest need.

You can check the progress of California AB890 here.

Despite the cost, our current healthcare system leads to the worst health outcomes for patients of any OECD country.

Despite the cost, our current healthcare system leads to the worst health outcomes for patients of any OECD country.

Circle Medical Providers must meet all of the following standards:

-

Exceptionally qualified in their field

-

Board-certified

-

Deeply empathetic for patients

-

Follows evidence-based care guidelines

-

Embracing of diverse patient backgrounds

-

Impeccable record of previous care

400+ Primary Care Providers.

100% Confidence.

No matter which Provider you choose, you will be seen by a clinician who cares deeply about your health and wants to help you live your happiest, healthiest life.

Circle Medical Providers are held to an exceptionally high standard of compassionate, evidence-based care.

Book appointment